Blog

Most people will agree that today's copyright laws make no sense. Many of them would have a hard time explaining why. Here is my take on it.

1. If the only purpose of copyright laws is to create minimal conditions under which talented people are not going to refuse to create, then our copyright laws provide WAY TOO MANY unnecessary rights to copyright owners.

2. If, on the other hand, copyright laws are to protect the vulnerable party that, in absence of such laws, would be unable to sell the results of their work on their terms, then our copyright laws provide WAY TOO MANY “user” exceptions.

3. The worst thing about our laws is that they are expressly attempting to create a balance between the interests of copyright owners and users. Same as creating a balance of interests between rapists and their victims.

4. Before any meaningful debate about modernization of copyright laws can happen, there must be a debate on the foundational level as to WHY we have copyright laws at all.

| Categories: | Intellectual Property: | CopyrightIntellectual Property |

| Values: | Individual RightsPassion | |

| Additional Tags: | PhilosophyFair Dealing | |

Many new entrepreneurs dismiss the importance of having a sound IP strategy from the very start. The usual excuse is, “I’ll make sure my business starts making real money and then I’ll deal with this law stuff.”

I call it a lose-lose scenario. The two alternatives are: (1) the business never makes it; or (2) the business becomes successful, but immediately it finds itself defenseless against all those who want a free ride on its success.

Think about Coca-Cola – would they be where they are today if they decided to wait until they sold a few hundred thousand bottles before they figured out how to protect their most important assets - their know-how and trademarks?

If your business involves creation, use or licensing out of content and you do not have a meaningful IP strategy, then you are not being serious about your business.

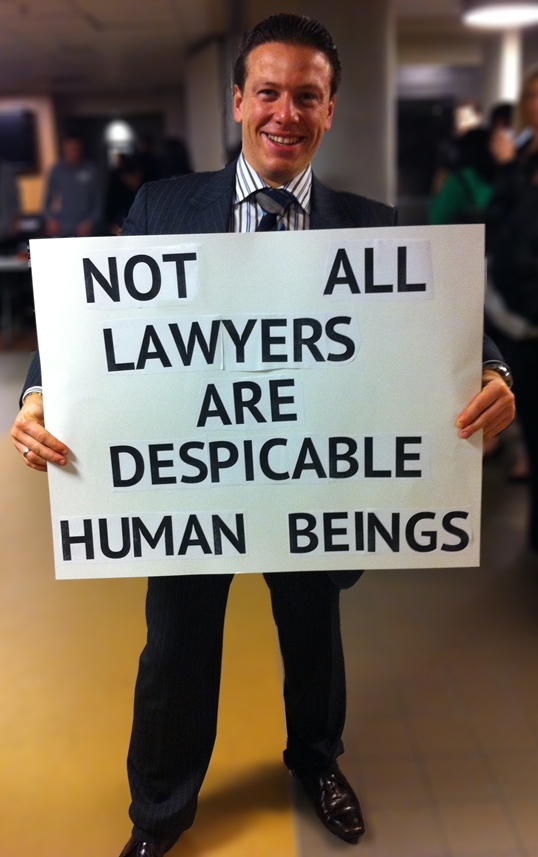

Just got back from Networking With Purpose event tonight.

Many great speakers. A lot of great guests. I had a brief presentation, too.

This time, I had more than just business cards with me...

Again Lego finds itself under an attack from Mega Brands, a Montreal-based competitor and maker of Mega Bloks. This time – in U.S. District Court in the Central District of California.

Lego owns a U.S trademark for the design of its world-famous blocks. Mega Brands claims that the trademark registration should be invalidated, which would allow Mega Brands to freely export its products to the United States.

The foundation of the claim is that what Lego has is not really a trademark. Rather, it is an attempt to obtain patent-like protection under the guise of a 3D trademark.

In simple terms, patents protect underlying ideas of inventions, while trademarks protect distinctive elements that allow the public to distinguish products and services of one business from products and services of another business. Trademark rights do not expire (as long as the trademark owner renews the registration on time), while patent rights only last for 20 years.

Common law courts have developed the so-called doctrine of functionality which prevents registration as trademarks of 3D objects, if such a registration would amount to protecting the functional side of these objects.

In Canada, the Trade-Marks Act makes it clear that “No registration of a distinguishing guise interferes with the use of any utilitarian feature embodied in the distinguishing guise.”

Interestingly enough, one of the leading cases in Canada dealing with the doctrine of functionality was the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Kirkbi AG v. Ritvik Holdings Inc., which happened to involve the same LEGO blocks.

Mega Brands’ representative stated: “Lego’s patents expired more than 20 years ago and courts around the world, including the United States, have ruled against its attempts to use trademark law for functional elements. Its claims have been dismissed by lower courts in numerous countries.”

In fact, it’s a tough call. Are the LEGO blocks nothing more than a “clever locking system” in the words of Mr. Justice LeBel? If the answer is no, what is it in the shape of the LEGO blocks that distinguishes them from any other blocks that would employ the same locking system? Can Lego protect anything but its own name and the higher-level designs?

Leaving the law aside for a minute, do you think it’s fair that Lego should lose its exclusive right to manufacture and sell its blocks? Please leave your comments.

‘Law’ means different things to different people.

For lawyers, law is about what is legal and what is illegal.

For academics, law is about what rules should exist to govern people.

For activists, law is a vehicle to achieve larger goals.

For most clients, however, law is seldom anything more than a matter of risk management.

If the potential benefits that a client may derive with a lawyer’s help are smaller than the lawyer’s bill, then there is no point in hiring the lawyer, even if from the purely legal standpoint, the strategy suggested by the lawyer makes perfect sense.

Likewise, there is no reason to hire a lawyer if the cost of hiring the lawyer in order to reduce or eliminate a certain risk is higher than the damage that the client may suffer multiplied by the likelihood of that risk ever materializing.

Lawyers who do not look at their work in context of their clients’ needs and businesses do their clients a big disservice.

Here is a short case study that illustrates how I do things differently.

A TV channel wanted to use a song in one of its productions that would only be broadcast once. The channel invited the song’s composer on the set to talk to the audience about the song. The arrangement was that no money would be paid to the composer for his appearance or for the use of the song.

From the purely legal standpoint, the only correct way to deal with this situation was for the parties to enter into a very detailed license agreement depicting what the TV channel did or did not have the right to do with the song. Drafting such an agreement and then negotiating it with the TV station would have taken many hours of lawyers’ time. It would have also created a document that neither of the parties really needed.

What I suggested was that the parties act on a handshake – without any agreement in writing at all.

It meant that the composer could legally sue the channel at any time for unauthorized use of his song, thus ensuring that the channel would not want to use the song outside that one specific production. On the other hand, I made it clear to the TV channel that if it only used the song as stated (that is, only as part of the production of which the composer was an integral part), then the composer would never sue it for what was technically unauthorized use – because it would ruin his reputation as a reasonable and trustworthy person, while the potential award that he could receive in the result of a potential litigation was minuscule.

The channel agreed. No written agreement has ever been concluded. The show aired as planned, once. Combined legal costs of both parties were very close to zero.

Context matters.

Categories:

Intellectual Property:Trademarks

Intellectual Property

Copyright

IP Strategy

TMF Cartoons

New Article

Patents

Domain Names

Internet

Values:

Passion

Integrity

Innovation

Decency

Efficiency

Freedom

Individual Rights

Website Updates:

Website Updates

More Cases Uploaded

New Feature

Tags:

CollectivismPhilosophySmall BusinessNew Copyright ActFair DealingArchive:

March 2016October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

March 2015

August 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

August 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011