Blog

Sep07th

2012

From now on, you can find interactive links to my blog comments regarding amendments to the Copyright Act on the page with the redline version of the Copyright Act.

This will make navigation even easier.

| Categories: | Website Updates: | Website UpdatesNew Feature |

| Additional Tags: | New Copyright Act | |

Sep06th

2012

One of the apparent attempts to modernize the Copyright Act is the addition of new Sections 27(2.3) and 27(2.4). These section are designed to outlaw services that encourage piracy over the Internet. Usually, these provisions are referred to as anti-torrent and anti-file-sharing provisions.

Section 27(2.3) contains the general rule:

”It is an infringement of copyright for a person, by means of the Internet or another digital network, to provide a service primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement if an actual infringement of copyright occurs by means of the Internet or another digital network as a result of the use of that service.”

Unfortunately, the wording of the rule is not very clear as to the scope of its application.

Let’s break it down into pieces:

– A person will be deemed to infringe copyright

– if that person provides a service by means of the Internet

– if such service is provided primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement

– if an actual infringement of copyright occurs as a result of the use of that service.

What remains unclear is whether “an actual infringement of copyright” and “it is an infringement of copyright” must refer to the same copyright owner.

Here is an example.

What if a person provides a service primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement in respect of works of copyright owners A, B, and C. The works in respect of which the service is provided are respectively A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2 and C3.

What if there has only been “an actual infringement of copyright” in respect of the work B3?

Who can sue the service provider? Will it be only copyright owner B because it was his work in respect of which there was an actual infringement? Or can this also be A and C, because the service is provided for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement and their works happen to be available through that service? Or can this also be D, Y and Z, simply because the service is provided for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement?

If the universe of plaintiffs is limited to B, the next question is whether B can sue the service provider in respect of all works or only B3?

As I wrote in my comments on the new Section 27(2.2), there is no such thing as a copyright infringement in general, there must be a copyright owner whose copyright is being infringed.

There are two possible interpretations here:

1. Section 27(2.3) sets out that in addition to the general rule that the copyright owner should sue the actual infringer, the copyright only can also sue the service provider, but only if that service provider has truly misbehaved by setting up a service primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement. In other words, if the service is not provided primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement, then the copyright owner cannot sue the service provider even with respect to the work that had actually been infringed via that service. However, if the service is provided for such a lowly purpose, then the copyright owner may, but only with respect to the work that had actually been infringed, also name the service provider as a defendant.

2. Section 27(2.3) sets out that one actual infringement is merely a trigger that attracts general liability of the service provider to ANY copyright owner whose works may happen to be infringed via the service.

The second interpretation appears to be overly broad. Moreover, its usefulness would be questionable since copyright owners whose works have not been actually infringed would hardly have suffered any damages in the result of the provision of such services, and according to s. 38.1(1.1), statutory damages would be unavailable to such copyright owners.

On the other hand, the first interpretation doesn't really add any meaningful remedies to copyright's owners arsenal. In fact, it only narrows them down by defining what copyright owners would otherwise refer to as infringement of their exclusive right to “authorize” some of the acts that only the copyright owner has the right to do. Therefore, this provision does very little, if anything, to provide to copyright owners additional protection against services primarily designed to enable acts of copyright infringement.

Section 27(2.4) contains list of factors (presumably, non-exhaustive) that courts may consider in determining whether a service provider has infringed copyright. There are a total of 6 factors:

1. whether the service provider marketed the service as one that could be used to enable acts of copyright infringement;

2. whether the service provider had knowledge of a significant number of actual infringements;

3. whether the service has significant non-infringing uses;

4. whether the service provider can and does in fact act upon reported acts of copyright infringement;

5. whether the service provider benefits from the copyright infringement;

6. whether the service would be economically viable if no acts of infringement were carried out through it.

These factors will allow the courts to recreate a good picture of the service provider’s role in the copyright infringement.

The problem is that once the court recognizes that the service provider is up to no good, there aren’t many new tools that the copyright owner would have against such a service provider.

BOTTOM LINE: Essentially the new provisions clarify that if you have created a service that is primarily designed to enable acts of copyright infringement (for example, you have a torrents engine), then as long as end-users are using your service to infringe upon someone’s copyright, then your acts are deemed to be unlawful authorization and thus copyright infringement. Because of an attempt to use overly broad language (presumably, with a purpose to catch more infringements), the Parliament had to balance it with planting several restrictions that severely limit the value of the new sections.

| Categories: | Intellectual Property: | Copyright |

| Additional Tags: | New Copyright Act | |

This is another section of the amended Copyright Act that is written in a language deliberately overcomplicated to such an extent that it would obfuscate even the most law-abiding citizens.

Essentially it introduces secondary infringement liability for certain uses of what is defined as a “lesson”.

Let’s start with this definition. There is no definition of a “lesson” in subsection 27(2.2). Such definition is found in subsection 30.01(1). The definition in subsection 30.01(1) starts with the following words: “For the purposes of this section…”

Question: what happens if a definition is given for the purposes of one section but is referred to in a different section? Was it really that difficult to place the definition of a lesson where it belongs – in the Definitions section (s. 2)?

Furthermore, here’s the full definition:

”For the purposes of this section, ‘lesson’ means a lesson, test or examination, or part of one, in which, or during the course of which, an act is done in respect of a work or other subject-matter by an educational institution or a person acting under its authority that would otherwise be an infringement of copyright but is permitted under a limitation or exception under this Act.”

Translating this into human-readable language, the term “lesson” only refers to such features of the educational process that involve unauthorized use of other people’s works, which use would have been deemed infringing if not for some limitations or exceptions found elsewhere in the Copyright Act. In other words, “lesson” does not cover lessons, tests, or examinations during which no unauthorized use of copyrighted works occurs.

Now, let’s go back to s. 27(2.2). The opening paragraph reads:

”It is an infringement of copyright for any person to do any of the following acts with respect to anything that the person knows or should have known is a lesson, as defined in subsection 30.01(1), or a fixation of one:”

Before I go to the list of the acts that are deemed to be an infringement of copyright, my first question is, it is an infringement of WHOSE copyright and in WHICH work? Are these acts infringing the copyright in the works that have been used without authorization to make up the “lesson”, or does section 27(2.2) refer to the entire lesson as a work of copyright presumably owned by the educational institution? Who can claim this secondary infringement – authors of the works used by educational institutions without authorization or the educational institutions themselves?

In a separate post on the new Section 30.01, I will provide my comments regarding the added exceptions and limitations relating to a “lesson”. For now, I will simply mention that the overall idea of that section is to allow educational institutions and their students certain unauthorized uses of copyrighted works so long as they occur as part of the “lesson”.

So we get this wonderful circular logic: a “lesson” is something that contains what would have been counterfeit works had there not been provisions in the Copyright Act that would render the use of such works non-infringing. It is not an infringement of copyright for the educational institution, the teachers or the students to do certain acts in respect of the “lesson”. And it is a secondary infringement of copyright to do certain other acts in respect of the “lesson”.

Typically, the idea of the secondary infringement of copyright presupposes that there is also the primary infringement. Section 27(2.2) virtually copies the previously existing section 27(2), which lists certain acts that are deemed to constitute secondary infringement of copyright if such acts are done with respect to a work or other subject-matter that “the person knows or should have known infringes copyright”.

By definition, inclusion of works in the “lesson” does not infringe copyright. If there is no primary infringement, how can there exist a secondary infringement?

As to the list of what constitutes secondary infringement, the first 4 items on the list are only marginally different from the wording used in Section 27(2), and refer to selling, renting out, distributing, exposing, offering for sale, exhibiting in public, and possessing for the purpose of doing any of the above.

There are also two added acts that are deemed secondary infringements with respect to a “lesson”. The first is communication by telecommunication to anyone who is neither a student enrolled in the course of which the lesson forms a part nor anyone else authorized by the educational institution. The second added act is the circumvention or contravention of (a) measures to destroy any fixation of the lesson; (b) measures to limit the communication by telecommunication to students and other authorized persons; and (c) measures to prevent students from fixing, reproducing or communicating the lesson beyond what is allowed under Section 30.01.

There is obviously a significant number of uses that do not fall within the scope of what is authorized under Section 30.01, yet do not fall within the scope of what is deemed to constitute a secondary infringement under Section 27(2.2). So the interpretation question is then, if going beyond what is allowed by Section 30.01 constitutes a primary infringement of copyright, why was there the need to duplicate the provisions of Section 27(2) in Section 27(2.2)? Alternatively, if Section 27(2.2) provides an exhaustive list of what can be deemed infringing in respect of a lesson, what is the legal status of the acts that are neither authorized in Section 30.01 nor prohibited in Section 27(2.2)?

The only reason why we will have such incomprehensible language in the Copyright Act is the quest for the compromise without an understanding of underlying reasons for the existence of copyright, in the name of securing an impossible balance of interests between copyright owners and those who care to use their works.

BOTTOM LINE: This is either a horribly inefficient way to say the right thing, or a convoluted way to say a horrible thing. Either way, this is BAD.

| Categories: | Intellectual Property: | Copyright |

| Additional Tags: | New Copyright Act | |

As I’ve just mentioned, Mincov Law Corporation has just celebrated its first birthday.

Not only do I have tons of great friends among founders and co-founders of Vancouver tech startups, I know the challenges surrounding running a startup firsthand.

For many startups the cost of getting a trademark through a trademark agent may be prohibitive, so they end up without a trademark or with a poorly drafted trademark application.

I want to extend a helping hand and announce that throughout September of 2012 Mincov Law Corporation will be offering its most comprehensive trademark registration package valued at $3,500 + HST to any business that has been incorporated for less than 2 years in Canada for only…

Become the next  ,

,  or

or  for half the price in September!

for half the price in September!

| Categories: | Intellectual Property: | Trademarks |

| Values: | IntegrityPassionDecency | |

| Website Updates: | Website Updates | |

| Additional Tags: | Small Business | |

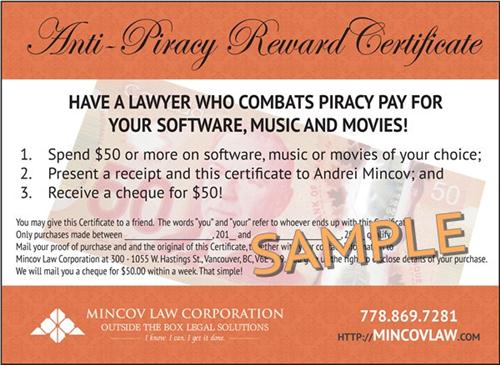

I have been fighting against unauthorized use of other people’s music, software and movies for more than 18 years.

However, I also am very much aware of the ease with which one may download pretty much anything today – for free and often more useable compared to the legitimate copy (greetings, DVD menus and advertising).

Once you’ve been using a cracked or a ripped file without any issues, it is very difficult to force yourself to shell out hard earned money for something that would not result in any positive change in how we use the software, listen to the music or watch the films.

I also know that most people would prefer to own legitimate copies of the stuff they have on their computers if somehow miraculously they didn’t have to pay for it, at least to the extent that their user experience wouldn’t be worse off compared to what they’ve had with the file they leeched off a torrent.

Financial incentives are often more convincing than words.

This is why it is my pleasure to announce that starting September 1, 2012 every new client of Mincov Law Corporation will be receiving Anti-Piracy Reward Certificates.

The idea is simple:

1. become a client of Mincov Law Corporation;

2. receive valuable legal advice and outstanding customer service;

3. get a reward certificate;

4. buy legitimate software, music or movies;

5. receive a cheque from your lawyer.

The certificates may be regifted.

And think of it, doesn’t it sound great: “I just got my lawyer pay for my music”?

Please comment and share if you like the idea.

Categories:

Intellectual Property:Trademarks

Intellectual Property

Copyright

IP Strategy

TMF Cartoons

New Article

Patents

Domain Names

Internet

Values:

Passion

Integrity

Innovation

Decency

Efficiency

Freedom

Individual Rights

Website Updates:

Website Updates

More Cases Uploaded

New Feature

Tags:

CollectivismPhilosophySmall BusinessNew Copyright ActFair DealingArchive:

March 2016October 2015

September 2015

July 2015

March 2015

August 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

August 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013

January 2013

December 2012

November 2012

October 2012

September 2012

August 2012

July 2012

June 2012

May 2012

April 2012

March 2012

February 2012

January 2012

December 2011